I awoke on August 9th to the heartbreaking news that my beloved friend of more than thirty years, Eugene Burger, had left us. He profoundly and personally influenced my work and my life, and the work and lives of countless magicians around the world. I grieve that I will never hear his living voice again, a voice that lives vibrantly in my heart and head, and doubtless forever shall.

Back in December I wrote one of my first Take Two essays about Eugene (No. 6), which includes two performance videos.

He wrote me to thank me and say, among other things, that the piece had “brought a tear” to his eye. And now as I write this, it is his turn to bring many a tear to my own.

In recent days I find myself overwhelmed with memories, of conversations both easy and hard, funny and serious, and always loving. We spent countless times together in person, at conventions, at lectures, at his home, on the phone. And every time there was magic to it, and there were laughs—oh my, the laughter. Truly he was one of the wisest and most loving men I have ever known. I am privileged to have called him a friend.

I know his life was a rich and satisfying one, truly a life fulfilled, a life lived the way he wanted to live it, and indeed, within the inescapable circumstances, ended in his own way as well. There is no greater success than that. But still, I grieve for the loss. I truly loved this man. Allow me to share some memories.

It was 1982 and I was at my friend Peter Samelson’s loft apartment in Manhattan. I noticed a little paperback pamphlet, with a black cover, and an odd title for a magic book: Secrets and Mysteries for the Close-up Entertainer.

“What’s this?” I asked.

Peter shrugged. The book had been sent to him by a mutual friend, a woman who knew the author. She had performed with him in some theatrical séance and spook show that he had created and performed in his native Chicago.

I didn’t recognize the author’s name: Eugene Burger. And neither did Peter, who so far had only glanced at the little book. Being a compulsive consumer of conjuring literature, I asked to borrow it, and he said, “Sure.”

That little book changed my work, and my life.

In 1982 I was only about a year in to my career as a professional magician, my third career path, although I’d been involved with magic since childhood. I had changed careers mid-life (like Burger himself, I would later discover), and I was trying to figure out how to make a living as a close-up magician. Along the way I had taken a year off to practice, attended bartending school, and was now bartending and performing at a restaurant in Greenwich Village.

But it seems I carried with me an unspoken, indeed unconscious bias about how to perform close-up magic. I had grown up watching some of the greatest masters of the art: Albert Goshman and Slydini, among others. Both these men performed close-up magic in a formal kind of staging, as one sees it at the Magic Castle in Hollywood, namely seated at a table, joined by two audience members, who serve as proxies for the larger audience.

As it happens, my friend Peter Samelson, who was a significant influence in the course of my decision to “go pro,” also performed in this classical manner—and so, although I had spent much of my life never leaving the house without a few small magic props or coins or a pack of cards in my pockets, performing in casual social settings since childhood and throughout my adolescence and beyond, I nevertheless think I always believed in the back of my mind that “real” close-up magic, serious close-up magic, had to be performed in that classical, formal fashion at the table. Performing at cocktail parties, doing “strolling” magic out of my pockets, was the way I was trying to make a living, but felt like a second-class format of sorts.

Until I read Secrets and Mysteries.

And read it. And read it. And read it again. Over and over and over and over for the next year or two, burning its lessons into my brain and heart, and putting them in practice out in the world of my performance art. I’m still practicing those lessons today.

Part one of the book—the “Secrets” of the title—included some of the oddest sub-titles I’d ever seen in a magic book:

- Drawing the Line

- Names

- Contact

- Not Hearing

- Energy

- Silence

- Discipline

- It’s Done With Mirrors

- Hecklers

I learned about the power of using a person’s name, part of the importance of connecting with people in the performance of close-up magic—connecting with them rather than performing at them. I learned about touching people as part of making that connection. I started thinking about silence, and the dramatic pause.

And even though I had been writing elaborate, carefully detailed scripts since my adolescence, I began to think about scripting and close-up magic in a different way. Because in the second part of the book—the “Mysteries” of the title—were provided magic routines and tools and devices (many of which continue to influence my work today), all of which began with a simple routine for performing magic with sponge balls in strolling conditions. And the scripting, while minimal, was fabulously effective.

I soon purchased my own copy of Secrets and Mysteries, which I would continue to read repeatedly—fifty times? A hundred times? I am no longer certain—and I found myself constantly drawn to Phil Willmarth’s introduction, and these words (emphases per original):

“Eugene believes that the challenge of performing is to make ‘that puzzle’ into a fun-filled and entertaining romp or a stunning, emotional experience.”

This challenge was mind-bending, and inspirational. Wandering in a party, tugging at elbows, with card tricks and little sponge balls? Really? Could this be achievable?

“His aim is to have ‘only strong effects’ in his repertoire. How well he has succeeded was attested to by England’s Bob Read after I had taken him to see Eugene work at a local bistro: ‘He’s marvelous,’ Bob said. ‘Every item’s a closer!’”

And that was saying something, considering that Bob Read, already an influence and inspiration for me (and eventually destined to become a dear friend), was one of the strongest performers I’ve ever known.

And thus my life, and my work, forever changed.

Eugene Burger: Sponge Balls

In November of 1984, I had my first chance to meet Eugene in person. He was doing a lecture in Long Island, and I took the Long Island Rail Road out to suburban parts unknown, well beyond the confines of New York City, and managed to make my way to the lecture.

At the end of the event, I offered to ride the train with him back into Manhattan. I asked him a question about his routine, “A Voodoo Ritual,” which I was performing by then, with a script very close to his own. It led to a long and thoughtful conversation about mentalism, and how and why Eugene and I shared an interest in this branch of magic, but preferred (at the time at least) not to actually perform it, preferring conjuring, or occasional close-up magic that touch on soft mental effects, or “mental magic,” to pure mentalism.

I had brought my copy of Secrets and Mysteries with me, and asked Eugene to sign it. It reads:

For Jamy

With appreciation for an intelligent conversation.

Eugene 11/84

And thus began a deep and important friendship.

In that lecture, Eugene mentioned that at the time he had 28 tricks in his working repertoire. “Down from 43—I’m moving in the right direction!”

This was profound to me. By then, I had also studied Eugene’s second booklet, Intimate Power. Plus he had taught a few more items, from notes I purchased at the lecture: Audience Involvement, a Lecture. And so the thought occurred to me that, using what I knew of his routines from these manuscripts, along with pieces he spoke about in the lecture, I might be able to reconstruct a list of perhaps three-quarters of his entire performing repertoire. This prospect filled me with wonder and excitement, not because I would want to do many of these, but because I could barely think of another example of knowing that much about a working performer’s entire repertoire, and that I might be able to glean valuable lessons from such knowledge.

So I created the list. And then, I studied it. And studied it some more. And eventually, I came to two significant insights, which led to important impacts on my work, and subjects about which I would eventually write in my essays and books. One was an insight about technique and method, that I detail in my essay, “Good Trick, Bad Trick” in my first book, Shattering Illusions. But the other, more important discovery, was this: That with only two exceptions of very quick and visual magic, every routine in Eugene’s repertoire included some kind of direct audience involvement.

This truly was revelatory to me. There was virtually no “Oh see the pretty thing!” material in Eugene repertoire—the kind of knuckle-busting visual magic that I (like so many magicians) love to watch and had spent countless years practicing, but often remain challenging to try to make engaging for real audiences. No matter how minimal in some cases, Eugene seemed to either select material that depended on audience involvement (for starters including any trick that required a spectator to select and perhaps sign a card), or he created presentational strategies in order to induce that involvement. Back then, before he hit upon his signature presentation about Hindu mythology as accompaniment for the Torn & Restored Thread, he was doing a more straightforward version of the trick, and I found it remarkable that he had taken what was traditionally a piece of purely display magic and instead had found a way for his audience assistant to be directly involved, by squeezing the ball of torn thread pieces between two fingers, as a magical gesture and a way of providing the magic moment—in other words, the spectator was achieving the magic. Wondrous!

And so I set about reconstructing my own repertoire, demoting those routines that lacked this critical element, featuring routines that relied upon it, trying to find ways to add it to other material in my repertoire, and searching for new material that effectively incorporated audience involvement.

That was the result of a single lecture, a first meeting, and fewer than two years of studying as many pamphlets. Imagine his impact after more than thirty years of friendship.

I can’t tell you every story. I couldn’t if I tried. I can’t tell you ever lesson learned, either. I can tell you something about his strength and generosity of spirit.

In 2000 I was the guest presenter at the Sylvan Magic Academy, in the Tuscany region of Italy, where I taught a four-day intensive seminar to a small group of registrants. Returning home from that experience inspired me to think about trying to create something similar in the United States. The only existing model here was Jeff McBride’s Mystery School, which was several years in at that point, and which Eugene was a part of, becoming Dean of the school. I had as somewhat different style of concept in mind, but was having difficulty solving several issues for myself regarding a couple of key decisions. I was also initially disinclined to ask Eugene for advice, in case he might have considered my plans some kind of competition. But after banging my head against a nagging question or two for a time, eventually I dialed his number and explained what I was thinking about. I said that I hoped he wouldn’t mind seeking his advice under the circumstances, and that I’d understand if he preferred withholding counsel.

Instead, he solved my two issues in one phone conversation, and thus my Card Clinics were created, and I produced a number of them around the country in the early and mid-2000s.

A more serious issue arose between us some years earlier, in 1995, early in my 18-year tenure as book reviewer for Genii magazine. Although I was always and remain a tremendous fan of Eugene’s books, he had collaborated on a book with another author, Bob Neale, entitled Magic and Meaning, of which I had a somewhat mixed opinion, and in particular was critical of some of the Eugene’s portions of the book. I wrote the review, and then in one of only three such cases in my eventual 18 years of reviewing, I called the author before the review went to print. I ended up reading the review to Eugene over the phone, and he was immediately and unhesitatingly gracious, and thanked me for a thoughtful review, and for the phone call, and encouraged me to run the review intact, assuring me that, among other things, it would have no impact on our friendship. I didn’t lose many friendships over those 18 years, but there were a few, and other such conversations had gone differently. But that’s not the most memorable part of this story.

What I came to discover after some time had transpired was that for a period of about a year following the review’s appearance, Eugene deliberately spoke about my review in every one of his lectures, during his discussions about elements of Magic and Meaning. I know it was every lecture because he told me so. And what he said in every lecture was essentially this: That while every other review of the book had been unreservedly positive, and while my somewhat mixed review had been the only one to raise any criticisms of the book, my review was his favorite—because, he said, I had “engaged with the ideas of the book.”

This says so much about him, without, I think, the need for further explication on my part. And I tell this story not to say anything about my own work, but rather, about Eugene—not just about the artist and thinker and writer, but above all, about the man. (And perhaps a little about the friend, too.)

How much of an impact did he have on me, and on my work?

It is virtually immeasurable.

In my early days of performing and bartending in New York City, I was inspired by Eugene’s superb pamphlet, Matt Schulien’s Fabulous Card Discoveries, which fired a lifelong professional obsession with the card-in-impossible-location plot. In particular, I began to work on the Card in Matchbook, and the routine I eventually developed would become a staple of my repertoire when I moved to the Washington D.C. area in 1985 to become the Magic Bartender at Bob Sheets’ Inn of Magic. I also developed a version of the Corner in the Glass, and Eugene’s “Voodoo Ritual,” from Audience Involvement, was a piece I would do probably once most nights, treating it as a special item. And truth be told, his “cocaine cigarette”—socially inappropriate today but perfect at that place and time—became a local trademark. We once got a phone call at the Inn: “Is the guy with cocaine cigarette working tonight?” A few years after the Inn of Magic closed, I was still recognized in Washington D.C. by a former patron who remembered that piece in particular.

In 1986, Eugene wrote Spirit Theater, a book detailing his Chicago “Hauntings” séance shows, and in its wake in the ensuing year no less than three such shows were independently produced around the country, significantly influenced by that book. One of those shows was a production I co-created with D.W. “Chip” Denman, one of my co-founders of the National Capital Area Skeptics (NCAS), and with NCAS as producers, Chip and I, adapting significant elements from Spirit Theater but also adding a great deal of our own original work, collaboratively performed a week’s worth of séance shows.

In early 1987, when I set out on my early career doing magic lectures, I was an unknown quantity, presenting a somewhat non-traditional, theory-laden lecture. I was inspired in this by the revolutionary path that Eugene had forged in the early ‘80s with his uniquely thoughtful and theoretical lectures, which, while my own lecture was substantially different in tone and style and technical content, unmistakably gave me the confidence to attempt my own approach. My Card in Matchbook—“Wish Fulfillment”—was a feature piece of the lecture. And when lecture promoters and bookers who had never heard of me—meaning most of them at that time—would ask me to describe my lecture, I’d often ask them if they’d seen Eugene Burger lecture. And if they had, I would say that in my lecture, “The lyrics are similar but the music is different.”

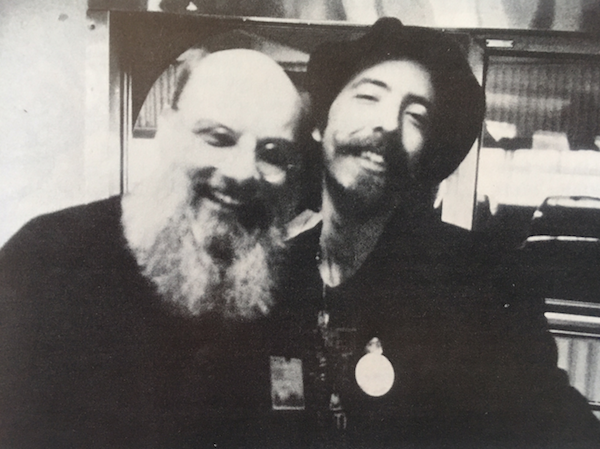

Eugene would also serve as a palpable presence in both my cover issues of Genii magazine. In the first, September 1987, I referenced Eugene’s essay, “On Imitation,” from the Matt Schulien manuscript, and included a photo of Eugene and I at the conclusion of my feature section. And in the second issue, in May of 1994, I included a conversation between Eugene and I about a subject of longtime mutual interest, namely teaching magic. (You can find that conversation here.)

On a whim I just ran a search in a digital copy of my first book of essays, Shattering Illusions, published in 2002, an expanded collection of essays that I initially wrote for Genii magazine in 1993/94. In the book, Eugene is referenced 83 times. About once every three pages or so.

A measure, of sorts, of that immeasurable impact.

There were certainly other tricks and techniques that would come and go from my repertoire over the years, initially fired by something Eugene had written or lectured about. In the late ‘80s he did a series of specialized workshops that only a small handful of people were fortunate enough to attend; I did so twice, and those techniques and some of the routines remain in my repertoire today.

When a magician would ask Eugene what new trick he was working on, he would often say, “New? I’m still trying to get the old ones right!” There was a deep and powerful lesson in that, a lesson that drove not only Eugene’s own work, but also his teachings for others. Here is a portion of what Eric Mead posted on Facebook shortly after learning of Eugene’s death:

Among the many many (many!) important things I learned from Eugene Burger, was the truly transformative notion that originality doesn't only mean new plots or new methods. Eugene provided a crucial example to me at a formative period in my career that originality in the performance of standards could be as powerful--or more so in some cases--than the novelty of original effects. Performance, context, connecting with people, and sharing what's meaningful trumps all else.

And Eugene’s work was full of such examples, of refining the old, as well as developing the new. I have a box with every gimmick Eugene ever used in the development of his “Shotglass Surprise,” well before he ever considered marketing it, as he shared his experiments and explorations, and a new version would arrive in the mail now and again. Eventually he worked out the final version, and one time in Chicago, perhaps one of the times I stayed at his apartment, he took me down to his local retail source where he initially found the stackable plastic shotglasses he was selling, and I bought a load of them. A version of the trick resides permanently in my close-up case.

And there were things he would share, for sake of discussion, for sake of learning, for sake of teaching. A time when he tipped the details of a marvelous mystery to me, one that he had fooled countless magicians with, including me. “I’ll show it to you now,” he said, “But you can’t use it until I’m dead.” We laughed, but we also knew he was sincere. Those words keep echoing around my head in recent days, bashing and banging off the drained emotional walls of my brain.

And the last trick of his I worked on, just last year, was something that I had been thinking about, and periodically experimenting with, for decades, a classic close-up trick that he had first discussed in another early booklet, The Craft of Magic and Other Writings in 1984. I emailed him about it, because he had published a number of variants that he had developed over the years, and I was looking to check in on his latest work. We engaged in a thread of 16 emails about the trick, along with a couple of phone calls. Truly, he was always trying to get the old ones right.

An Old Carnival Game

Even as I have shed tears daily and nightly this week over Eugene’s death, what I constantly keep hearing in my head is his laugh. So many of my friends and colleagues have commented on this specifically in recent days. A friend texted, “Can’t believe I’ll never hear him laugh again.”

It was a truly marvelous laugh, a laugh that reflected his entire self and spirit, a laugh of joy, of mischief, of a deeply engaged life. In my memorial tribute to Tom Mullica last year in M.U.M., I recounted the story of the hardest I ever laughed in my life. It occurred due to an unintentionally hilarious interaction with Tom, but it took place in Eugene’s convention hotel room, and we all shared in that laugh for a long time.

In the 1990s, Eugene and I talked frequently on the phone. Among other conversations, we got into the habit for a few years of deconstructing television magic specials, such as “The World’s Greatest Magic” and other programs produced by the Canadian attorney and amateur magician, Gary Ouellet. When the second “World’s Greatest” special aired in November of 1995, Eugene and I got on the phone as was our habit. We took our time working through the acts, what we liked, what we didn’t like, what might have been better, what we most enjoyed.

On that special, the penultimate piece was Melinda’s debut of the “Drill of Death.” It was basically a Spiker illusion done with a massive, and inescapably phallic, drill bit. Eventually the conversation reached that subject, and I said, “So: Melinda.” To which Eugene responded, in his inimitable fashion: “Puh-leaze. Can you say: CONTEXT? Somebody?”

We laughed. We roared. And we kept laughing for a very long time. One word, and a wealth of ideas communicated. “Context?”

In the aftermath of Eugene’s death, countless magicians are sharing their stories, their appreciation, and their grief. An interview with Eugene (find links below), conducted by Andrew Pinard in 2009, and usually residing behind a pay wall, was released for free to the community, and I watched it—as I said to a colleague online, “I’m just listening to him, and revisiting. And in the midst of my grief, thinking about the ideas he challenges us with.” In that interview Eugene says that he never derives humor at the expense of a spectator, nor at the expense of himself. Think of that: He does not make fun of himself, because he has no intention of diminishing himself or, equally if not more importantly, the magic. I have quoted countless times over the decades Eugene’s statement that if you want your audience to take what you do seriously, you must first take it seriously yourself.

And in the same interview and similar vein, he says that he never ends his performances on a laugh. Rather he makes a point of ending every close-up show on a serious note, because this is what he wants the audience to take away from the experience. He wants them to take the magic seriously, and he wants them to remember that.

I’m not sure that among Eugene’s many invaluable and insightful lessons, any one of them was ever more important than that one. Eugene spent his life—in his generous, gentle, loving manner—fighting tooth and nail against the trivialization of magic. Fighting above all for excellence—for, as he says in this interview, doing things “magnificently.”

Eugene spent about fifteen years of his life performing in restaurants, at patrons’ tables. It’s a specialized and very challenging form of close-up magic—all the more so if you want to have an impact and hope for your work to be taken seriously.

When he was working at a place that was adjacent to a Chicago theater—I think the restaurant was called the Café Versailles—I had the opportunity, at his invitation, to come by one evening and watch him work, subtly following him around at a distance as he went table to table, and also performed at the bar. It was a magnificent opportunity, filled with lessons. One of the best moments was when a group half his age and somewhat liquored up were getting a bit loud and interruptive. He paused, looked at the young woman leading the charge, met her eyes, and said, “My … we’re a little …frisky, tonight … aren’t we?”

That’s all it took. She sat up straight, like an elementary school kid who had just gotten his hand slapped. And she behaved quite well for the rest of the show, and everyone in the group enjoyed it.

The three clips I’ve posted here in this piece are all from that phase of his work, all material he was performing in restaurants. I love this brief clip because it’s exactly how he would often begin those shows at the tables. (And how he would keep people from messing with the prop box.)

Acrobatic Matchbox

Of course there is more I could say, so many more stories I could tell. But I’ve already gone on too long, and it suddenly now dawns on me that it is because I am conjuring him up for myself here, battling to bring him back to life, bring him here beside me for just even a moment, a moment to hear that laugh again, to see his smile … to say good-bye. I realize that the moment I stop writing the magic will go out of it, he will fade away out of my reach, forever, and I will be left here crying, again, yet another day.

Eugene used to say he was living on borrowed time anyway, that he never expected to make it past fifty. After that it was all a bonus, he said. But we didn’t believe it, I didn’t believe it, and I never wanted him to leave. And now he has. And now I do have to say goodbye. And thanks. And thanks. And goodbye.

And I don’t want to. I just … don’t … want to.

More on Eugene

This two-part interview of Eugene by Andrew Pinard is particularly rich with many cogent examples of Eugene's thinking and ideas, and eminently quotable. It is quite suitable for non-magicians as there is little if any technical jargon and no discussion of methods. Part 1 | Part 2

MORE: TAKE TWO ARCHIVE