Any magician with an interest in large-scale illusions, the history of magic apparatus, or magical automatons, will already be familiar with the name of America’s premiere illusion builder, John Gaughan. John also collects antique magic apparatus, particularly of the 18th and 19thcentury, and he possesses a rare specialty in restoring antique “automata,” mechanical figures that were often featured in magic shows in the 19th century.

John Gaughan grew up in Dallas and became interested in magic at an early age. Hanging around the magic shop he met then local magic celebrity Mark Wilson and his wife and assistant Nani Darnell, who were doing a local live television series, a prelude to their eventual national platform on The Magic Land of Allakazam, the first network magic series, which many of my generation grew up watching.

As a young adolescent, John and a friend went to work for Wilson, assembling magic kits and helping to set up and break down their portable stage for regular free weekend shows for the public. So Gaughan would see the backstage and production side of professional magic at a very young age.

He also performed through high school at birthday parties and the like, while also playing music, which was in fact his major in college. But performing magic would not be the focus of his continuing work in the field. After college he headed to Los Angeles where he again when to work for Mark Wilson, this time helping out on “Magic Land of Allakazam,” while he also continued his education, moving on from music to industrial and furniture design. It would turn out that he was building a foundation for his future life in magic, which was also contributed to by his contact with Owen Magic as part of his work for Mark Wilson. When the TV series eventually came to an end, John continued working for Wilson on the road, working long hours driving nights between locales, and working long days of setup and breakdown for the never-ending road shows.

For a time John would teach furniture design at Cal State Northridge, and his expertise in building furniture would continue to mesh well with his magic activities and interests. Between his years of working for Wilson and also his work with Owen Magic, eventually John was ready to set out on his own as an illusion builder. A big project with Harry Blackstone, Jr. helped set him on a successful path running his own business, and he continued to work with Wilson when the latter became an advisor to the Bill Bixby TV series, The Magician. Gaughan would also become Doug Henning’s illusion builder after Henning broke through with The Magic Show on Broadway, working with Doug’s illusion designers and advisors, Charles Reynolds and Jim Steinmeyer. This would begin a career-long relationship with Steinmeyer—if Gaughan is America’s premiere illusion builder, Steinmeyer is our premiere illusion creator—that continues to this day.

In time, Gaughan’s client and project list would become an A-list resume, including movies, television, Broadway shows, rock stars, and amusement parks. He’s built illusions for Jim Morrison, Alice Cooper, Earth Wind & Fire, Elton John, Michael Jackson and more. He created the box for the film “Boxing Helena” that made it appear as if the lead character, played by Sherilyn Fenn, lacked limbs, and did similar service creating the illusionary wheelchair for Gary Senise in Forest Gump.

And needless to say, Gaughan has also worked with every top magician of our time, including Siegfried and Roy, Lance Burton, David Copperfield, Criss Angel, Ricky Jay, David Blaine, Cyril Takayama, and many more. His depth of knowledge about the history of illusion technology deeply informs his modern constructions, particularly when it comes to areas of special interest like levitations. His work on Lance Burton’s signature levitation, for just one example, was based in a history that goes back more than a century (and one of its earliest original progenitors sits on view in his workshop).

The intersection of illusions and magic history was perhaps most fully realized—in addition to his astonishing personal collection of apparatus and automata—in Gaughan’s collaboration with Mike Caveney and Jim Steinmeyer (and initially, Ricky Jay) to create the Los Angeles Conference on Magic History, which ran biennially from 1989 through 2015, concluding (or pausing as the case may be) after fourteen of the invitation-only gatherings that featured historical lectures and performances of legendary restored or recreated illusions.

Perhaps the most remarkable example of these historical performances took place in 1993 and again in 2007, when Gaughan, along with his collaborators and co-producers, recreated the legendary Hooker Rising Cards. Dr. Samuel Hooker was an amateur magician and inventor who presented magic shows of his original creations in his Brooklyn brownstone home at the turn of the century. The world’s greatest magicians sought entry to witness the unique performances, in which, among many effects, a deck was shuffled by a spectator, then placed on a small table and covered with a glass dome. As audience members randomly named cards, the called for cards would mysteriously rise from the pack, some even floating to the top of the glass. Without exception, every great magician of the time was completely baffled by Hooker’s creations, and they all left written testimony to that effect.

Historical accounts of the Hooker performances read like mythology, and magicians wondered for decades if the reports were largely hyperbole. But through a sequence of fortunate events, John Gaughan eventually obtained the original apparatus from Dr. Hooker’s grandson, and then painstakingly pieced together the apparatus and the effects it was capable of creating. Eventually John, along with Steinmeyer and Caveney, presented a twenty-minute performance of some of Hooker’s effects, in a complete reproduction of the room in which Hooker had performed his mysteries, in his Brooklyn residence a century before. No magician who got to witness the Hooker recreation will ever forget it—including this writer—and the reality lived up to its legend as probably the greatest continuing secret in the world of magic. (I wrote about the History Conference and some of its illusions in my review of The Conference Illusions by Mike Caveney.)

I recently visited John in his workshop on a family trip to LA which I described in another article, The "J-Pa Knows a Guy" Tour.

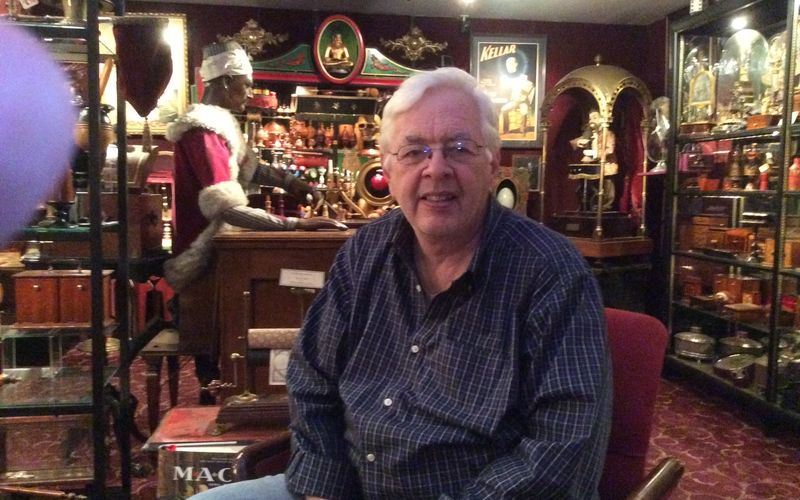

Talking with John is always a pleasure. His low-key, soft spoken gentlemanly affect belies the powerful intellect and master craftsman skills that lie just beneath that affable surface. He builds illusions his own particular way, generally with full-scale constructions rather than computer simulations or miniature models. He emphasizes that real-world performance is vastly different than theory on paper or screen, and thus his old world skill set delivers the most modern of solutions for every conceivable variety of need and application. I literally cannot imagine the skills it requires to restore or recreate the automata that fuel Gaughan’s passion, but I am truly wondrous every time I see one of his performances with them. And above all, perhaps, I am constantly reminded, and filled with respect, for the underlying love of beauty that permeates his work. Sitting in a chair amid his wondrous collection—like stepping into a reality version of the film Hugo—and chatting about magic past and present, is a rare and soul nourishing experience. If you ever get the chance, I highly recommend it.

John has made countless television appearances, and been the subject of many interviews both on and off camera. Here are some selections I’ve made from among the many.

Here’s a brief introductory look at John’s collection:

The legendary “Turk” turns out to be more of an illusion than an automaton, an astounding creation considering when it was invented. It still fools people today, and its design presaged important illusion principles still in use today.

One of my favorites of John’s many automata is Antonio Diavolo, the little trapeze artist. This first video is of John presenting Antonio on a Ricky Jay television special. Unfortunately the resolution is poor but you do get to see all of John’s interactions with the puppet. The second video lacks John’s interaction and narration but does provide clearer close-up views of the automaton.

Psycho is a truly historic automaton with a stellar history in the world of magic. While this performance may seem a little slow, it was a miracle in magic shows of the day, and remains quite mysterious even today in what the automaton can accomplish.

Bonus Clip

If you’d like to take a closer walk through the John Gaughan collection, here is a guided tour John gives to magician Scott Wells, in two parts.

And finally, while there is plenty of press to be found about John, here is a nice interview from 2012 with Joshuah Bearman in which John discusses The Turk among other things.

MORE: TAKE TWO ARCHIVE